By

President de Gaulle of France initiated the secret operation “Vide-Gousset” and repatriated 3,313 tonnes of gold reserves from the vaults of the Federal Reserve in New York and the Bank of England in London from 1963 until 1966. De Gaulle feared America’s deficit in its balance of payments would rupture Bretton Woods and lead to a devaluation of the dollar against gold.

All France’s dollars were converted into gold, and to avoid treachery, the metal was repatriated over the course of three years. It took 44 boat trips and 129 flights to bring home more than three thousand tonnes of gold to the Banque de France in Paris.

France’s decision turned out extremely well. As was foreseen by the French, the price of gold in dollars increased sharply, from $35 to $800 dollars an ounce, from 1968 until 1980 — the dollar lost 96% of its value against gold. Countries that held on to their dollars were less fortunate.

More recently, after the Great Financial Crisis, the Banque de France repatriated 211 tonnes, upgraded all its bars to current wholesale standards, overhauled its vaults, revived Paris as a trading hub for institutional investors, and history repeats itself as we are in a gold bull market presently.

At a conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944, delegates from 44 allied nations forged a new international monetary system. An agreement was made on a system of fixed exchange rates and free trade. Currencies were tied to gold via the dollar, as the Federal Reserve promised to buy and sell gold at a fixed price of $35 dollars per ounce, and foreign central banks had the obligation to keep their currencies within the “par values” to the dollar 1.

The greenback was seen as “good as gold” because dollars could always be converted into gold at the Federal Reserve (Fed). And thus, next to gold, foreign central banks would hold dollars as international reserves, which made the Bretton Woods system comparable to the “gold exchange standard” from before the Second World War.

The newly erected International Monetary Fund (IMF) was to supervise Bretton Woods and support countries with short-term balance of payments deficits by lending reserves. With approval from the IMF, countries could devalue (revalue) their currency in case of persistent balance of payment deficits (surpluses) to restore equilibrium.

In 1959, former General of the French military Charles de Gaulle became the President of France and sided with his most influential economic advisor, Jaques Rueff. Rueff and de Gaulle were vocal critics of Bretton Woods and America’s “exorbitant privilege.”

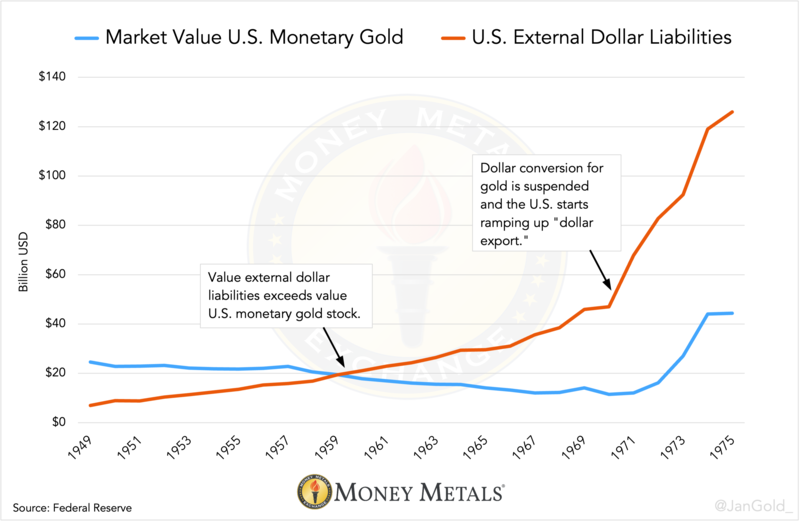

Bretton Woods allowed the U.S. to pay for imports with dollars it created out of thin air, as the system inherently made foreigners need dollars as a trade, intervention, and reserve currency. Only foreign central banks could redeem dollars for gold at the Fed if the Fed allowed them to2. In addition, exported dollars caused inflation abroad as central banks were obliged to defend their exchange rates and thus had to print currency to buy dollars.

The United States was running a balance of payments deficit (more money was exported than imported) since the 1950s, which made U.S. official gold reserves decline — foreign central banks redeemed part of the imported dollars at the Fed. A tipping point was reached in 1960 when America’s external dollar liabilities exceeded its monetary gold holdings, prompting global concern regarding convertibility.

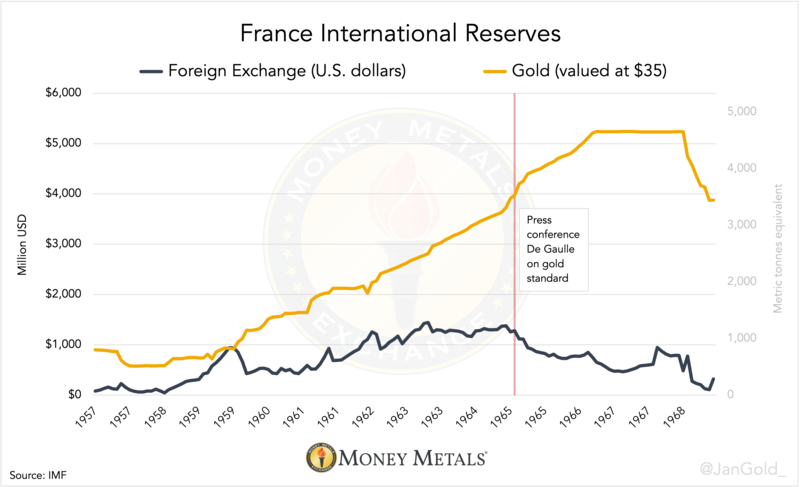

In the decade from 1958 through 1968, France experienced strong economic growth and had a balance of payments surplus, generating an increase of its international reserves. In 1961, Rueff, as well as other advisors to De Gaulle, theorized that Bretton Woods couldn’t survive because central banks eventually would be unwilling to hoard dollars as the U.S. was running out of gold. The United States would be forced to either devalue the dollar against gold or suspend gold convertibility.

De Gaulle and his team painfully recalled what happened in 1931 when the U.K. devalued sterling against gold in a similar fashion, causing the Banque de France (BdF) to suffer a loss of 2.35 billion French francs, twice the size of its capital. The French Treasury (taxpayer) had to step in to bail out BdF.

France became more reluctant to accumulate dollars despite the interest dollar holders earned.

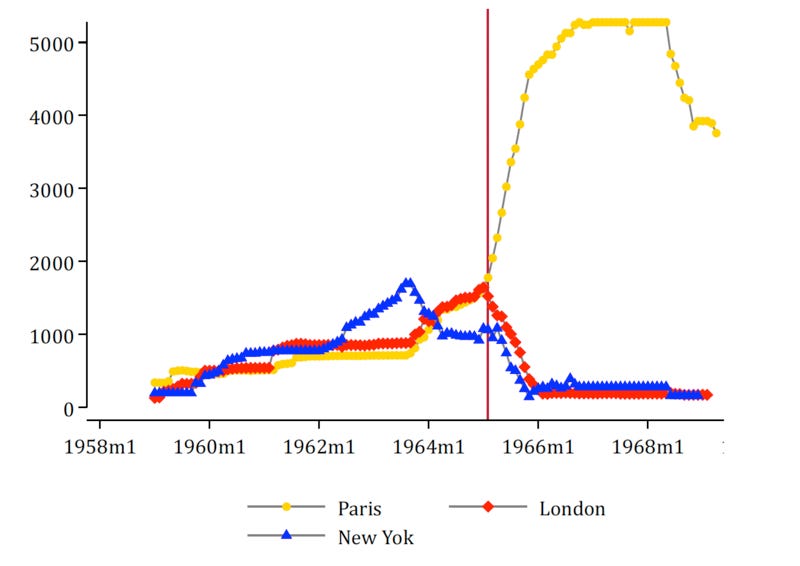

By November 1961, after the dollar gold price had briefly spiked in London, Fed President Alfred Hayes presented a plan at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Bazel, Switzerland, to jointly stabilize the price of gold in the free market (Bordo et al. 2017). European central banks assented to form a “Gold Pool” with the U.S. to buy and sell gold in the London Bullion Market with the objective of keeping the price at $35 dollars. France accepted to join on the condition the U.S. would fix its balance of payments deficit (Avaro, 2022).

Even as France had pledged to cooperate with the Pool’s operations in London, BdF converted newly acquired dollars into gold at the Fed in New York. Consequently, its gold holdings in New York grew relative to those in London and Paris.

De Gaulle opined that American imperialism supported its capital export. In January 1963, he told his spokesperson:

Western Europe has become an American protectorate without even realizing it. We must now rid ourselves of their domination. But the difficulty here is that the colonized don’t really want to emancipate themselves. Since the end of the war, the Americans have subjugated us painlessly and without much resistance.

For the General, gold was also a tool to push back on America’s quest for domination, in which the dollar played a key role. Not long after, in March 1963, De Gaulle began to worry about the geography of the French gold and demanded that all of it was to be repatriated to Paris (Avaro, 2022). Any gold held abroad could be used as leverage against France.

Staff of BdF advised against repatriations, considering the costs of transportation and insurance. In a compromise, the secret operation “Vide-Gousset” was launched in September 1963 to repatriate 400 tonnes of gold from New York (Avaro, 2022; Bruneel, 2012).

Initially, transfers from New York were made by sea, as it was difficult to ensure transport by air. Involving the French Navy was considered, but that would have blown the operation’s cover. Instead, BdF used ocean liners from the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, capable of shipping 25 tonnes at a pace of two trips per month. Notably, not all gold repatriated went to Paris, some went to a BIS account at the Bank of England (BOE). It’s possible that BdF had engaged with the BIS in location swaps.

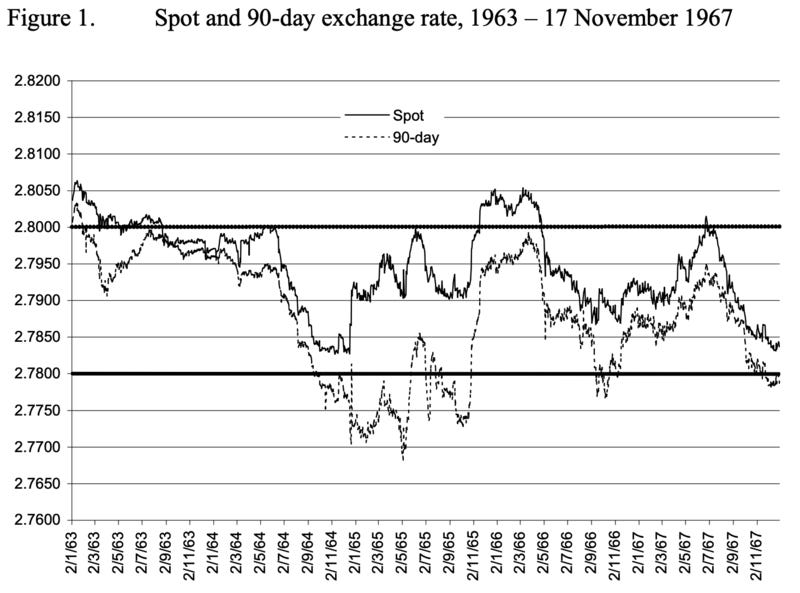

De Gaulle’s distrust of the U.S. for safekeeping the French gold went hand in hand with America’s ongoing balance of payments deficit. Great Britain, which De Gaulle viewed as an extension of the U.S., was experiencing a balance of payments deficit, too. Before the dollar, the pound sterling came under attack by speculators in 1964.

With pound sterling on the brink of devaluing, a dollar degradation became even more likely. From evaluating the finances of both America and Britain, the French took the decision to increase dollar conversion, accelerate repatriating gold from New York, and repatriate gold from London as well. The Banque de France was able to charter passenger planes from Air France to airlift gold from London to Paris starting in December 1964 (Bruneel, 2012).

The communication plan was to first announce one uncommon conversion of dollars; then, a French official would voice concerns regarding international monetary problems and demand America to reform. As planned, BdF publicly announced a conversion of $300 million dollars into gold (267 tonnes) in January 1965, which was followed by the General’s infamous press conference on February 4 at the Élysée Palace, where he advocated for a return to the gold standard. From the De Gaulle:

In the current system, the United States can go into debt for free, at the expense of other countries, because what the United States owes them from trade is paid, at least in part, with dollars only they can create3. Considering the serious consequences and the crisis that could arise from this situation, we think that measures should be taken to avoid this. We consider it necessary that international trade is settled, as was the case before the great misfortunes of the world [First and Second World War], on an indisputable monetary base. One that does not bear the mark of any particular country. What basis? In truth, nobody can really imagine any other standard than gold.

The supreme law, the golden rule that should be reapplied to international economic relationships, is an obligation to settle the balance of payments between one monetary zone and the next through deliveries and withdrawals of precious metals.

Right after his speech, De Gaulle suggested his colleagues send a “Colbert” missile cruiser to New York and pick up French gold in size 4. His Minister of Finance convinced him to give up on this idea as it could damage diplomatic ties inadvertently (Avaro, 2022).

The central bank of France proceeded with more dollar conversions and scheduled passenger and then cargo planes from Air France, capable of carrying roughly 30 tonnes each, to fly between New York and Paris in addition to the ocean liners. Repatriations were covered by the media at the time, but the size and details of the operations were unknown, as far as is disclosed in newspaper archives (source, source).

Chart 4. Distribution of France’s monetary gold (in millions of dollars valued at $35/ounce). The red bar represents the day of De Gaulle’s speech on the return to the gold standard. “Affaire 18” was the code name for repatriations from New York by sea, “Affaire 19” and “Affaire 20” were repatriations by air from London and New York, respectively. Source: A Gold Battle? De Gaulle and the Dollar Hegemony during the Bretton Woods era.

Within a year, nearly all of France’s gold was brought home. Though, as new dollars were acquired, the operation of Vide-Gousset expanded. In 1965 and 1966, no less than 94 air flights were organized, which allowed the repatriation of 1,175 tonnes of gold from London. A total of 1,638 tonnes were recovered from the U.S., divided over 24 boat trips and 35 air flights. In aggregate, 3,313 tonnes were repatriated, according to Honorary Director General of the Banque de France, Didier Bruneel, in “The Secrets of Gold” (Les Secrets de l’Or).

As imbalances in the global financial system kept growing, France saw no other option but to drop out of the London Gold Pool in June 1967. Later that year, the U.K. was forced to devalue pound sterling, and markets began eying the dollar next.

Slowly but surely, things started getting worse, and the Pool was confronted with substantial losses. From March 8 through 14, 1968, the gold syndicate had to sell almost 1,000 tonnes of gold to cap the dollar price of gold. “U.S. air force planes rushed more and more Fort Knox gold to London, and so much piled up in the Bank of England’s weighing room that the floor collapsed,” writes Timothy Green in “The New World of Gold.”

On March 15, 1968, the U.S. ordered the London Bullion Market to be closed for two weeks, and the Pool’s operations were terminated. Thereafter, a two-tiered gold system emerged: the price of gold was allowed to float in the free market, but the official gold price was unaltered at 35$ dollar. Private entities could trade gold at the free market price, and central banks could transact among each at the official price while not being allowed to sell in the free market. Of course, no central bank would sell gold to another central bank for $35 dollars, knowing the actual price was higher.

Ironically, the French franc came under pressure later in 1968, and BdF sold gold chiefly to defend its currency, as it had converted most of its dollars (see chart 1). De Gaulle’s successor, Georges Pompidou, devalued the franc in 1969.

Although it was still possible for European central banks to convert dollars into gold at the Fed under the two-tier system, the Americans would intimidate or blackmail them not to. Finally, President Nixon closed the gold window on August 15, 1971, due to requests by France and Great Britain to exchange dollars for precious metals.

Bretton Woods de facto ended in 1968, but it stumbled on until 1971. Aside from formal changes in the IMF’s Articles of Agreement that were implemented down the line, the era of floating exchange rates began in 1971.

Due to raging inflation in the 1970s, the gold price went up from $35 dollars per ounce in 1968 to $800 in 1980. That’s an increase in the dollar price of gold of 2,200% or a dollar devaluation of 96%, whichever way one prefers to look at it.

France not only accurately predicted the devaluation of the greenback against gold, but it also acted appropriately by converting as much dollars as possible when it could. Repatriating the gold was not only to pressure America to reform but also to prevent uncomfortable outcomes. And virtually all French monetary gold is still stored in La Souterraine, the BdF’s vault in Paris.

In 2018, BdF’s Second Deputy Governor, Sylvie Goulard, published a remarkable article in the Alchemist: “Banque de France and Gold: Past and Future.” First, Goulard reminds her readers of the fact that Paris was an important gold trading hub next to London and New York during the classical gold standard in the 19th century. She continues by stating that “the financial crisis [in 2008] acted as a wake-up call for gold,” which “proved to be an opportunity for gold and for the Banque de France.”

This “wake-up call” prompted the Banque de France to upgrade all its monetary gold to current industry standards between 2009 and 2018, making sure all bars can be deployed in wholesale markets if needed.

Additionally, La Souterraine has been renovated: the floors have been strengthened to support heavy forklift trucks, new vault compartments in different sizes have been added for storing single bars or sealed pallets, there are strong rooms for handling, transportation, and auditing, and a modern IT system is integrated.

In addition to storing France’s monetary gold, BdF offers custody services and trading solutions (spot and swap) for institutional clients and, with the aim of conquering market share from London. Goulard mentions, “In 2012, the Banque de France began to extend its range of gold services to reserve managers.” What she didn’t mention was that France repatriated another 221 tonnes from London around 2015.

After decades of gold demonetization attempts by the U.S., the Great Financial Crisis has revived gold’s role in the international financial system as a reserve asset with no counterparty risk. The price is going up, and more and more central banks are buying gold (and more of it).

Meanwhile, there is a trend of nations repatriating gold, this year, gold has overtaken the euro to become the world’s second-largest reserve currency, while the East is increasingly parting with the dollar as a trade and reserve currency.

My assessment is that the French have once again correctly anticipated developments in the gold market.

The Federal Reserve acted as an agent for the U.S. Treasury, which was and still is the owner of the U.S. monetary gold.

For Germany, i.e., that had American troops on its soil, protecting it from the Soviets, it was “not done” to convert dollars for gold at the Fed. Germany did rapidly increase its gold reserves in the 1950s and 1960s, but mostly through the European Payments Union.

Holding foreign exchange is a loan to the issuer of that currency because that issuer still has to settle a trade imbalance with something real like gold.

I have not been able to find an official source on a French battleship ever arriving in New York to pick up gold.

Most information in this article was drawn from “A Gold Battle? De Gaulle and the Dollar Hegemony during the Bretton Woods era” and “Les Secrets de l’Or.” The full list of sources can be found below:

Avaro, Maylis. “A Gold Battle? De Gaulle and the Dollar Hegemony during the Bretton Woods era.” (2022)

Bordo, Michael, Ronald MacDonald, and Michael J. Oliver. “Sterling in Crisis: 1964–1967” (2009)

Bordo, Michael, Dominique Simard, and Eugene Nelson White. “France and the Breakdown of the Bretton Woods International Monetary System.” (1994)

Bordo, Michael. “The Operation and Demise of the Bretton Woods System; 1958 to 1971.” (2017)

Bordo, Michael, Eric Monnet, and Alain Naef. “The Gold Pool (1961–1968) and the Fall of the Bretton Woods System. Lessons for Central Bank Cooperation.” (2017)

Bundesbank. “Germany’s Gold.” (2018)

Bruneel, Didier. “Les Secrets de l’Or.” (2012)

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “The United States Balance of Payments 1946–1960.” (1961)

De Gaulle, Charles. Press conference February 4, 1965. INA and Youtube.

Graetz, Michael, and Olivia Briffault. “A “Barbarous Relic”: The French, Gold, and the Demise of Bretton Woods.” (2016)

Green, Timothy. “The New World of Gold.” (1982)

International Monetary Fund. “Articles of Agreement.” (1944)

Manly, Ronan. “The Trigger That Closed the U.S. Gold Window.” (2021)

Nieuwenhuijs, Jan. “France Has Repatriated All Its Monetary Gold.” (2022)

Nieuwenhuijs, Jan. “Gold Wars: the US versus Europe During the Demise of Bretton Woods.” (2024)

Nieuwenhuijs, Jan. “Saudi Central Bank Caught Secretly Buying 160 Tonnes of Gold in Switzerland.” (2024)

Nieuwenhuijs, Jan. “Nations in the mBridge Project Are Stockpiling Gold, Driving Up Prices.” (2024)

Rueff, Jaques. “The Monetary Sin of the West.” (1972)

TIME. “Money: The Gold War.” (1965)

Weston, Rae. “Gold. A World Survey.” (1983)

White, Lawerence H. “The End of Bretton Woods, Jacques Rueff, and the ‘Monetary Sin of the West.’” (2021)

Zijlstra, Jelle. “Dr. Jelle Zijlstra.” (1978)

Originally Published on Money Metals Exchange.